Essential Reading

A curated shelf of foundational works that shaped our approach to Meaning System Science and interpretation under constraint.

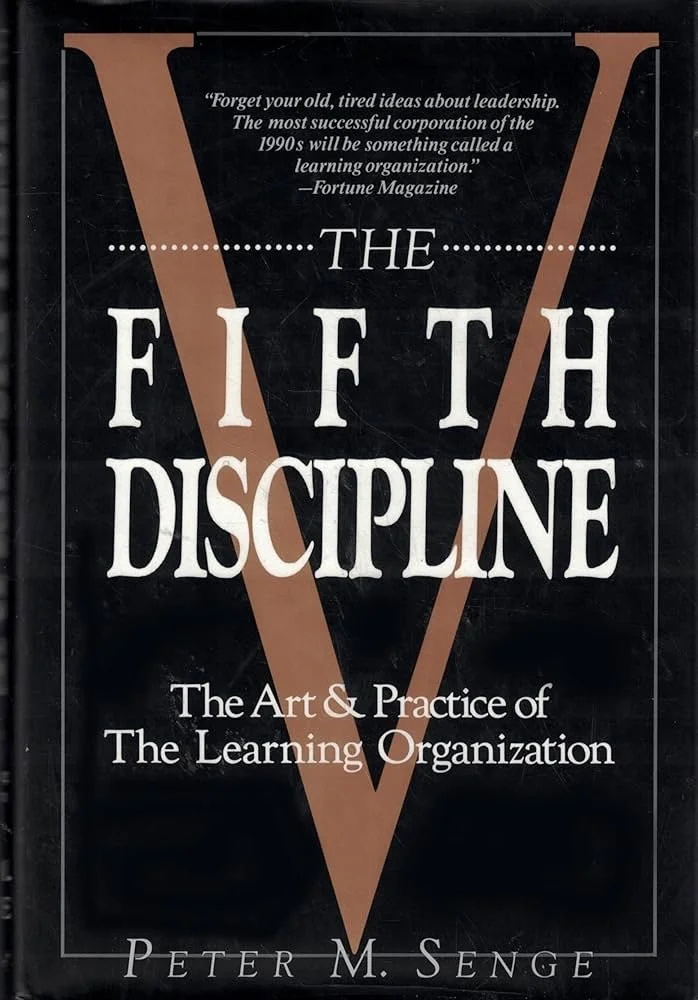

Featured Spotlight:

Peter Senge

The Fifth Discipline (1990)

Senge’s work examines how organizations become shaped by their own structures of attention, feedback, and learning, and how recurring patterns of failure persist even when information is available. It remains one of the most influential frameworks for understanding coordinated activity in modern organizations, particularly the gap between what is present in a system and what becomes consequential within it. Start here for a structural systems lens, then use the readings that follow to deepen analysis of interpretation, evidence, and closure.

At TMI, these are a few of the thinkers whose ideas most shaped how we approach interpretation. The rest of the list expands into additional authors we draw on across the field studies, measurement work, and governance framing.

(T)

(P)

(C)

(D)

(A)

(L)

First Law

TM

The TMI Research Library

These readings offer context. The Research Library offers the science itself. Explore our Curated Reading Paths.