The General Theory of Interpretation

1. Canonical Definition

The General Theory of Interpretation (GTOI) specifies the structural requirements under which interpretation remains reliable across interpreters, environments, implementations, and time.

GTOI treats interpretation as a system-level process constrained by reference promise, signaling, routing, correction, and closure behavior. Within an interpretive event, meaning becomes operational at binding: the threshold at which an interpretation becomes governing for action and begins constraining response pathways. It explains reliability as a property of a stated system object under stated constraints, not as a function of individual belief, intent, temperament, or local domain content. Under GTOI, valid interpretive claims must be stated within an explicit boundary and membership condition and evaluated through checkable traces such as reference artifacts, signal streams, decision pathways, correction behavior, and closure outcomes. After closure, governing meaning may persist under a post-closure meaning regime (PCMR or DMR) until Action Determinacy Loss (ADL) forces interpretive re-activation; these are governance and transition classifications, not event-internal commitment dynamics.

GTOI is content-agnostic: it governs the reliability of interpretation, not the correctness of any single conclusion.

GTOI is the Institute’s primary research program. It produces Meaning System Science (MSS) as its operational layer, and it is used alongside System Existence Theory (SET) and Transformation Science to evaluate interpretation inside admissible systems and across change attempts.

MSS specifies a minimal variable architecture for interpretive reliability: Truth Fidelity (T), Signal Alignment (P), Structural Coherence (C), Drift (D) as inconsistency accumulation rate, and Affective Regulation (A). GTOI states the general requirements. MSS makes those requirements measurable and comparable in real environments.

GTOI is distinct from domain-specific theories of textual, legal, or hermeneutic interpretation. It treats interpretation as a cross-domain and cross-substrate phenomenon class: wherever signals must be evaluated relative to a declared reference promise and routed into action under constraint, interpretive reliability is conditioned by the same structural requirements, even when implementation mechanisms differ.

2. Foundational Thinkers: GTOI cites prior work as lineage, not attribution. The thinkers below are included as antecedents for specific component conditions later formalized in the Meaning System Science architecture.

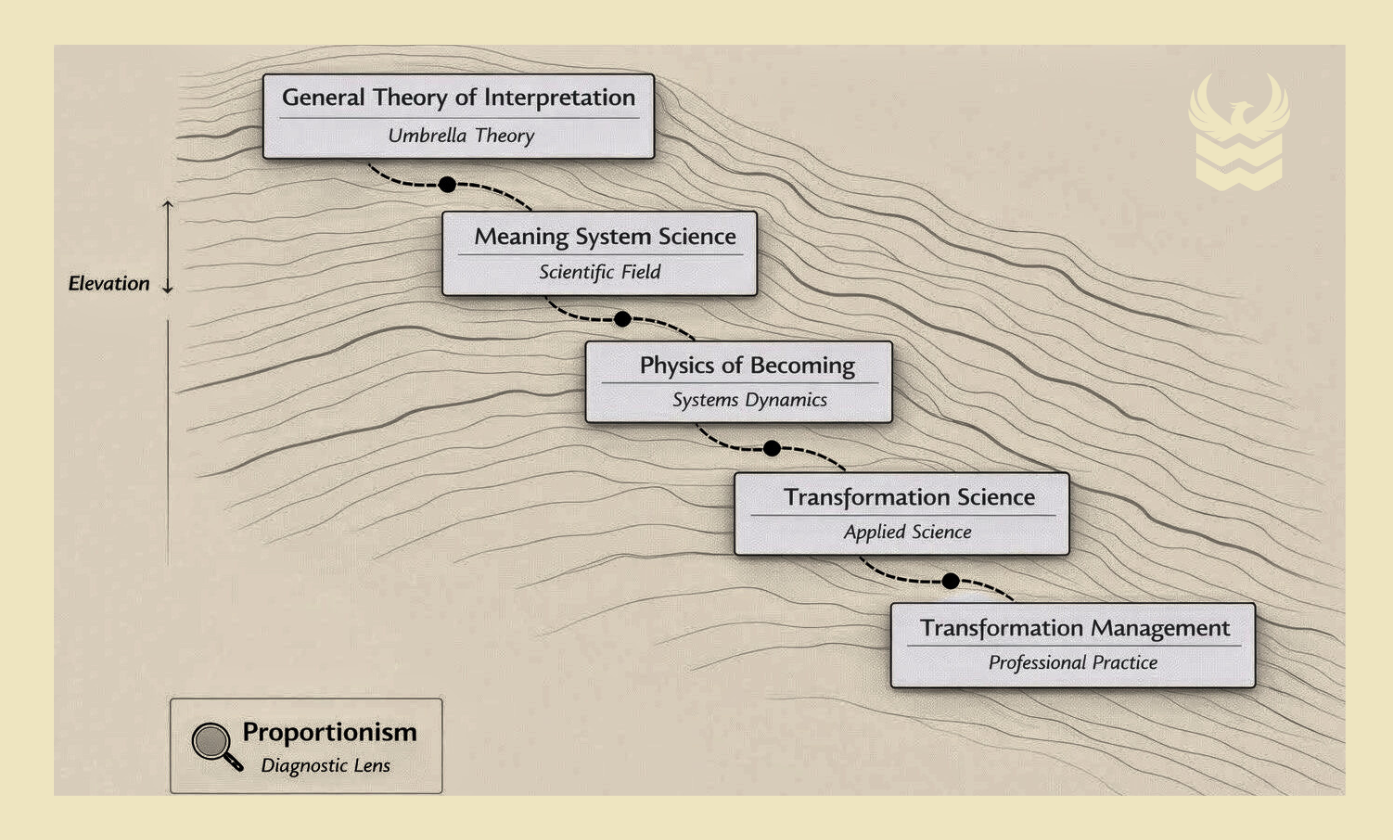

Figure 1. A map of the GTOI canon

The canon is organized as adjacent domains within one landscape, not a linear sequence. The path traces the core conceptual arc.

Figure 1. A map of the GTOI canon

These domains are connected regions of one landscape, not a required sequence; the path marks the main conceptual through-line.

3. Plainly

GTOI explains what must be true for a system to produce compatible meaning from the same conditions. It makes interpretation analyzable as a general system behavior across biological, organizational, institutional, cultural, and artificial environments.

4. Scientific Role in the General Theory of Interpretation

GTOI defines the constraint class for interpretation at scale. It:

defines interpretation independently of domain

specifies the stability conditions that enable coordinated action across roles and time

provides the theoretical basis for MSS variable architecture and law formation

GTOI defines what interpretation requires. MSS defines how those requirements can be evaluated in real systems.

5. Relationship to the Variables (T, P, C, D, A)

T, Truth Fidelity: stable reference conditions and verification discipline

P, Signal Alignment: convergent signals across roles, channels, and authorities

C, Structural Coherence: usable pathways and decision structures that distribute meaning consistently

D, Drift: rate of accumulated contradiction when stabilizers lose proportionality under load

A, Affective Regulation: regulation conditions determining update capacity and correction throughput under pressure

6. Relationship to the Physics of Becoming

L = (T × P × C) ÷ D

GTOI supplies the interpretive basis for legitimacy as proportional stability. It defines why drift rate relative to stabilizers is the governing condition for reliability at scale.

7. Application in Transformation Science

Transformation Science applies GTOI and MSS to systems undergoing change by modeling variable movement over time, proportional imbalance under pressure, and when accumulated drift requires structural reconfiguration.

8. Application in Transformation Management

Transformation Management operationalizes interpretive governance by designing decision environments that preserve shared meaning, maintaining alignment across roles and channels, and detecting rising drift rates before interpretive failure becomes systemic.

9. Example Failure Modes

identical directives produce incompatible interpretation because reference conditions differ

interpretations bind differently across roles or channels, producing incompatible routed actions from the same declared reference conditions

signals produce inconsistent action because authority cues vary across roles

pathways do not support consistent distribution of meaning across time

contradiction accumulation exceeds correction throughput, increasing drift rate

regulation capacity is insufficient for load, reducing update and correction performance

10. Canonical Cross References

Meaning System Science • Interpretation • Meaning System • Physics of Becoming • First Law of Moral Proportion • Proportionism • Legitimacy (L) • Truth Fidelity (T) • Signal Alignment (P) • Structural Coherence (C) • Drift (D) • Affective Regulation (A) • Semantics • Semeiology • Systems Theory • Thermodynamics (Meaning System) • Affective Science • Interface • Transformation Science • Transformation Management • Meaning System Governance